IN APRIL AND May of 1983 the people of Castlemilk, passing on their way to the shops or to pay their rent, became accustomed to the sight of the three gaily-decorated caravans tucked neatly inside the grounds of the offices of the Glasgow District Council Housing Management Department. It was a good spell of weather and excitement was high. ‘Sit in’ supporters patrolling the pathway alongside the caravans invited passers-by to sign their petition or make a small donation to the campaign by tossing whatever coppers they could afford into one of the bright plastic buckets which hung from the railings.

Inside the grounds, others busied themselves shaking out sleeping bags and blankets and hanging them on the railings, sweeping the steps of the caravans, lifting pieces of rubbish from the ground and when necessary feeding the two stray dogs who had attached themselves to the protesters. The smell of cooking from the caravans wafted in the air and the strains of music added to the feeling of excitement. Much good natured banter was exchanged and many tales recounted of experiences at the hands of the housing department.

During these weeks, the protesters patiently explained to those who stopped alongside why the caravans were there and outlined the events leading up to this strange situation.

On a Tuesday evening some weeks before, the three families who were the subject of the protest had been awakened from their sleep by some kind of explosion from the ground floor flat in the building where they stayed. This was quickly followed by a fire and when the Fire Brigade eventually rescued the families it was by turntable from the balconies of their homes. They had been given accommodation at Glasgow's Homeless Unit on a night to night basis, but eventually told that they would have to return to their homes the following Monday. The families were refusing to return. It was impossible, they said, to live in the houses in the condition they were in, but more importantly, they were convinced that the explosion had been caused by a petrol bomb being thrown into the ground floor flat. They were terrified of returning and insisting that they be rehoused. But housing officials had opposing priorities. In this ‘difficult to let’ area tenants had come and gone and close after close had been boarded up and remained unoccupied. The housing department now dug their heels in, determined that this particular close was not going to be added to their existing list. The houses were habitable, they insisted, and if a bomb had indeed been the cause of the explosion then thise was a matter for the police and had nothing to do with the housing authorities. Before the following Monday, a group of people had formed themselves in support of the tenants. The press and television had been contacted and photos had been taken of the ‘habitable’ houses. The local M.P. John Maxton had himself inspected the houses and had suffered breathing difficulties in the close and stairs without even entering the houses.

On the Monday, the tenants refused to move back into the houses and the Homeless Unit refused to give them further accommodation. On Tuesday the housing department did in fact respond by sending out the building and works who set to scrubbing down walls and stairs in an attempt to make the building habitable. Still the families refused to return and had their furniture removed and left with friends for safe-keeping. They themselves had to find accommodation from wherever they could. The group of supporters rapidly increased in number and harried councillors and housing officials without success. By the following week after a lengthy packed meeting in the Jeely Piece Resource Centre, a further course of action was agreed. The following day, the three families with friends and supporters, occupied the Castlemilk Office of the Housing Management Department and spent the day explaining to people why they wanted alternative housing and how this was being refused. At closing time those prepared to risk arrest remained in the office. This course of action continued for more than a week and each night the police were called in. Some nights, after being invited to leave by the police, the protesters would go, sometimes they wouldn't and sometimes they weren't given a choice but bundled into the police van. On one occasion the police arrived on foot, but unfortunately those arrested declined the invitation to walk the short distance to the local police station and a call had to be put out for the vans. Over a period of some eight days, 48 arrests were made, 12 people being arrested on four occasions. On the last occasion, the charge was ‘Breach of the Peace’ and as this was more serious than the previous charges of ‘Trespass’, court appearances were scheduled for 2 days later. The protesters made plans for a spectacular court appearance. Each of the 12 approached different lawyers, asking them to appear at court on their behalf. Posters and demonstrations outside the court were arranged and a Press Release was prepared. It was going to be an occasion! However on the evening before the court appearances, a policeman arrived at the offices of the Housing Department where he knew he would find the accused and produced letters for all informing them that their appearance the following day was no longer required. Nothing further was ever heard from the police regarding the 48 arrests they had made!

By this time however, tactics had changed and the next plan of action - the erection of tents, replaced a day later by donated caravans - quickly followed.

So, now after a couple of weeks, people had grown used to the sight of the three caravans in the grounds of the Housing Department. Most people were now aware that each caravan symbolised the shelter which the families had chosen rather than return to their previous homes.

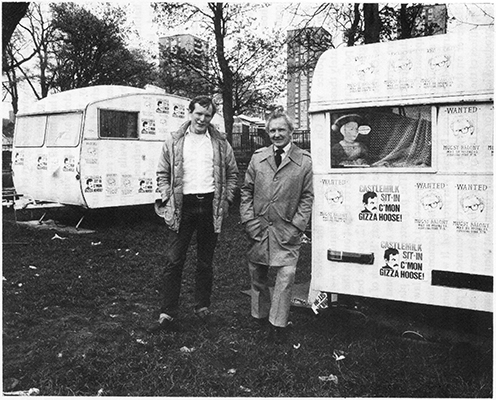

Posters caricaturing the recently appointed Director of Housing, Paul Mugnaioni, and reading ‘Wanted Mugsy Baloney, May be Posing as Housing Director’ were pasted all over the caravans. A slogan from a TV series was adapted and ‘Castlemilk Sit-In’ posters and lapel badges with ‘C’mon, Gizza Hoose’ were everywhere.

The protesters drew up a roster of volunteers for day and night duty, but the caravans were always full of people. Sleeping bags, blankets, food, cutlery were to hand and no-one was ever hungry or cold. Groups came along to entertain the ‘Sit-In’; local shops donated foodstuffs and some three weeks into the campaign a supporters dance was held. Still the Housing Department continued to argue that it was all a matter for the police and nothing to do with them. Still the caravans remained in the grounds and nobody attempted to move them or the people living in them.

Group meetings continued to be held daily, a visit to Mugnaioni was made and while all were aware the situation was causing headaches in political circles, it seemed that neither the Councillors, the Housing Department or the Director of Housing were going to be shamed into re housing the families and continued to insist it was a police matter. Rumours were in fact about that the Police Special Patrol Group were patrolling the area at night.

However like any good, well-organised campaign, more than one avenue was being pursued and so alongside the Gizza Hoose Sit-In, negotiations were going on with the Housing Management for re-housing, using medical grounds and similar tactics which allowed them to back down gracefully and so some six weeks after the fire, the three families had satisfactory offers of re-housing and victory was achieved. The six houses in the closes the tenants had come from remained unoccupied, was boarded up and a security guard posted in the area. The sit-in caravan occupation of the Housing Department had lasted almost four weeks.

Five years later many questions remain unanswered. Why the clamp down on publicity? At the beginning of the campaign while the protest was still fairly tame and no doubt following similar line to the respectable and acceptable community work exercise of petitions, posters, haranging the councillors, and the occasional orderly demonstration, the press and TV appeared really interested and used the material given. But once the tempo quickened and it became clear clear that this was not an easily controllable group following a community worker paid by the Council, but a real gut protest from able individuals of varying political persuasions of the left and many ordinary angry people prepared to take a stand against injustice, the media cooled off and while for a time reporters and photographers continued to arrive and were very interested, this did not find its way to the newspapers. Did the media really lose interest?

Why were the charges against those arrested dropped and the court appearances cancelled? Who made these decisions? Why were they made? It would seem that having the charges dropped required the agreement of the District Council, the Regional Council, the Police and the Courts. Was the establishment afraid that if word got about, caravans would be moved into similar sites in other housing schemes in Glasgow and perhaps the people in Easterhouse, Drumchapel or Pollok would also say “We prefer to live in an old caravan rather than accept the conditions you are forcing upon us!”

Or maybe indeed the wall of silence which surrounded Castlemilk and the unique happenings there had something to do with the embarrassing fact that the then Lord Provost Michael Kelly had just launched his much acclaimed ‘Glasgow’s Miles Better’ campaign. It was perhaps unfortunate that this coincided with Castlemilk’s ‘Gizza Hoose’ Sit-In, but one thing is certain: none of the photographs taken of the latter found their way into Dr. Kelly’s campaign publicity brochures!